Negative space in cycles

A helpful badge, morale boosts, weekday vertigo tedium, in pursuit of normal days

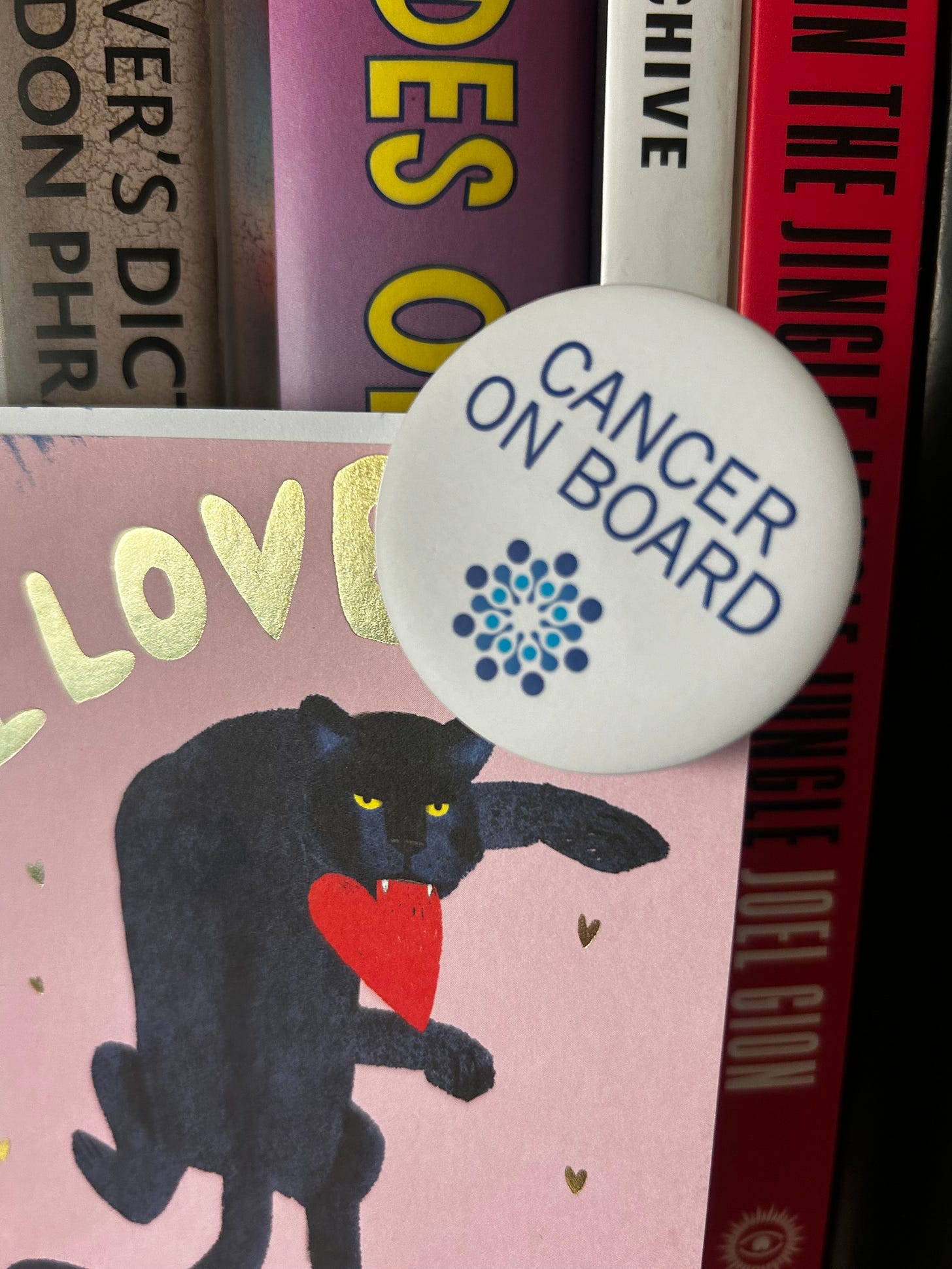

Last week, a Cancer on Board badge dropped through my letterbox.

Since the start of December I’d been looking for something to say that I might not be at my best right now. An afternoon trying to function whilst feeling particularly shaky had got me thinking, “I’m not yet OK.” Those days come and go unexpectedly — the signals of approach might be weak, but they can amp up in a finger snap before completely taking over. Sometimes it might be the brain giving up after a day of attempted work. Last week, it happened randomly when I sat down to play Super Mario Kart with my kids and my head flipped. Game over. Zéro point.

The badge is a touch bigger than the kind I’d normally pin on. To be fair, that’s possibly for good reason. Size matters. Like the Baby on Board badge given to pregnant women using public transport in London, it acts as a visible indicator that will hopefully make days easier and less pressured for someone suffering from illness. And there’s a lot of hope contained in something like that. On a good day, a seat might be offered on a bus, or a door might be held open for a few seconds longer. Small gestures like that can sometimes feel like being offered a lift after you’ve been trying to run across a busy motorway on foot.

On their website, the makers of Cancer on Board badges say that their message is about more than wearing it and signalling your current status: “Knowing you have one in your pocket, just in case, can be a morale booster.” I’ve not worn mine yet. Gratefully received, it sits in my coat pocket and hopefully gives my Ready Brek glow a touch more bright light.

Cancer has been playing on my mind over the last few months. Facing up to a cancer growth is extremely hard. It’s not a bad toothache, some overpowering gout or a poky dose of the flu. It’s a monstrous ogre that lurks inside one in two of us, each of whom will develop a bunch of abnormal cells determined to do their own strange, dangerous thing. Some people are lucky in treatment. Others become the story that sticks in your head — the paranoia, an awful puzzle that must be solved.

Chemotherapy’s long tail and the smudge left by cancer feel very much like the same thing, even though they are clearly not. My cancer was mainly chopped out in October 2024, yet it’s hard not to think of its lurking power when facing vertigo attacks. The mind doesn’t drift back to a bunch of foul-tasting pills, or the last few drops wrung from an intravenous fluid bag. It feels like cancer running its nails down a blackboard. A damn curse that’s still stuck right there inside of you.

On Friday, working from home with an ill daughter lying on the sofa, my brain seemed to explode. I spun, as if it had become untethered from the everyday to grasp its own frantic, chaotic freedom. There was no warning system in place. No badge to warn anyone that something bad was coming.

The day before, I’d been to the doctor to talk through a series of blood test results. She was optimistic about what had come back (note to drinking companions — liver and kidneys still working fine, amazingly), but said that the after-effects would continue for as long as the drugs took to drift out of the system. She also pointed out that one of the causes of the attacks may well be stress.

Although I’d found a safe mental space to surround myself with as the world around us falls to horror and madness, chaos fully erupted over an interview I’d set up for my day job. Everything sorted, all looked good — only I’d blanked that the writer and interview subject were an ocean apart. Five hours’ time difference. It all came unstuck. A pulse in my head rose from a ping to a furious explosion; a physical manifestation of psycho-stress throwing everything in the air with no hope or expectation that anything would be caught. Smash everything, leave a mess for some other sap to clean up.

God, I fucking hate writing about these attacks. It’s fucking tedious. Illness is tedious. Lying down to calm the mind in the middle of the day is tedious. For months, I pictured this period of recovery as a slow walk towards a brighter light in the distance — the glimmer of hope in the misery of a bleak, rainy winter. Instead, I’m trying to get my head around the worst vertigo attack I’ve had since giving up all of the bad drugs the hospital gave me, trying to work out how not to have another one, ever.

And that’s the problem. Off the drugs, on that slow walk, but the feeling remains the same. A perfectly normal work situation causes a seismic stress headfuck that sends you to bed for five hours. Your youngest daughter brings you toast to check you’re not in any real trouble. As she places it down, you’re too out of it to thank her. The tiredness that comes with it is the zero-power setting — legs that feel like they’ve run uphill marathons, the kind of oblivion zap you see on the face of a pensioner trying to find their way back from a Wetherspoons toilet after three pints of leaky piss.

Hated head hole, hated words to describe the tedium of it all. I realise now that this is how life is, and no one can tell you how long this blue phase will go on for. The badge can’t mentally help you deal with all of this. Maybe it’ll get someone to offer you a seat and reduce the stress by an inch or two, though.

I know this will end — I don’t need reassurance. I know things will improve. That brighter light on the horizon will grow and bring warmth with it. But honestly, when does spring officially start? Tonight I’m going to a school concert where the youngest is performing on stage. I’m very much looking forward to it. It’s good to know that, whatever happens, I’ll be holding the Cancer on Board badge in my balled fist the whole way through. I’m taking their positivity as a forward signal.

Note to self: promise that the next one of these won’t be so damn miserable.